To see that which is enlightened: Living the Light - Robby Müller (2018)

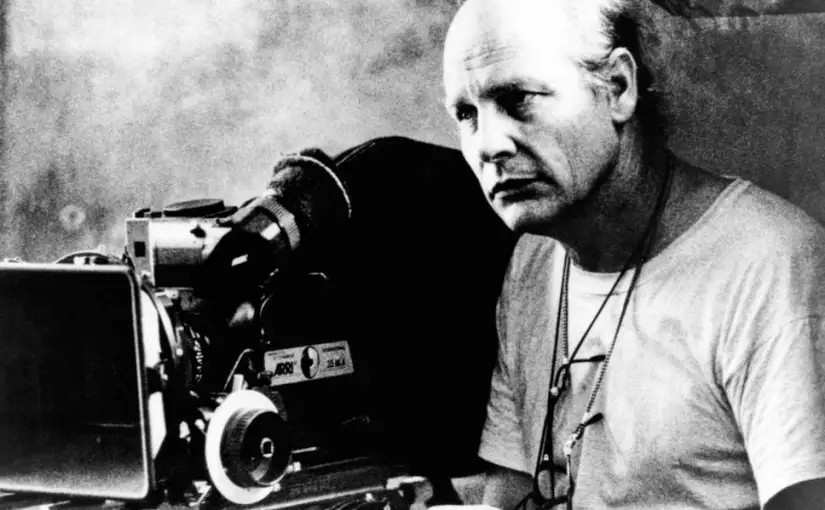

Light, for any cinematographer, is first and foremost a technical problem: how do you make sure that the scene’s action is adequately perceptible? At what point does the light’s brightness block out the detail of the shot? Beyond the technicalities, light exerted on Robby Müller a positively metaphysical attraction. When Müller died this summer (aged 78), cinema lost a relatively unsung hero. Luckily, we have Claire Pijman’s new documentary Living the Light - Robby Müller (trailer) to show us how light became for Müller an object of endless fascination, disarming and empowering him at the same time.

The symbolism of light is obvious, signifying purity, goodness, beauty, warmth, etc. Adding to that, these metaphors are also eminently political, as darkness acquires the meaning of depravity, baseness, death. But as Müller’s frequent collaborator Jim Jarmusch notes in the documentary, it is never really light itself that fascinated Müller, but rather the way it broke, reflected off surfaces, became diffuse and interacted with darkness. As the film opens, we see Müller filming a desert landscape with the sun on the horizon. The shot itself is clearly raw, unpolished, a quality that it shares with most of the private footage to which Pijman had access in making this documentary. What stands out, at first, is the way that the sun utterly blocks out any meaningful content that the shot might have until Müller’s fingers move down from the upper side of the frame to block out the direct sunlight. The shadow play that ensues, Müller moving his fingers back and forth across the beam of light in rapid succession, the kind of game that you might have played as a young child for mild amusement, suddenly and somehow gives the shot an elusive significance that brilliantly sets the tone for the rest of the film.

The glittering gold wrapping of a piece of chocolate, placed on his pillow in his motel room. The play of light on the surface of a shallow stream of water, disrupted, momentarily, by his dog walking through it. The faintest glow reflected off of Harry Dean Stanton’s face as he is driving a car, in Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984). It is shots like these, both from Müller’s professional works as well as his private archive, that lead Wenders to liken Müller to a ‘Dutch master’: Müller’s treatment of light being on a par with that of Johannes Vermeer. Pijman uses these shots to their fullest effect, showing them exactly how Müller shot them, uncut and often without voice-over. And though Müller himself too remains almost completely silent throughout the film, it is surprisingly easy to feel exactly the same fascination that he felt for the things he caught on camera.

To be fascinated is to be a slave to your own gaze. In a sense, it is to be utterly without control of your visual (and consequently your motor) skills. Those who have ever found themselves unable to look away from something will know what I mean. Yet, Müller’s shots exhibit a kind of playful, childlike freedom, as if they were the result of a careless throwing together of a couple of images, a fact noted by fellow cinematographer Agnès Godard. I shouldn’t psychologize, but it’s as if, through the mediation of the film camera, Robby Müller was able to turn his submission to his own gaze into a source of freedom. A white dove flies through the shot, causing Müller to immediately scratch any ideas he might have had for the shot, so that he can follow the bird around. Through film, Müller’s fascination for nothing but that which happens to catch his eye, becomes his liberation.

If there is anything about this film I must find fault with, it is this: Müller extensively and meticulously documented almost every aspect of his life, and it is clear that Pijman had access to all of it, but does that mean that we are entitled to see all of it? Some parts of the film feel unnecessarily intrusive, particularly those dealing with Müller’s family, though I am sure that Pijman had the full consent from the family for showing us these clips. We see clips from both Müller’s first and second marriage and through an interview with his daughter, the film leaves us with unanswered questions about Müller’s family life. More importantly, these questions seem out of place in a film that deals, first and foremost, with Müller’s singular relation to the sensible world around him. Whatever the merit of these parts of the film, I find that they do not really add to the portrait that the film already paints so brilliantly of Müller and his art. This portrait might best be described as Goethe once said of humankind: “determined to see that which is enlightened, but never the light itself”.