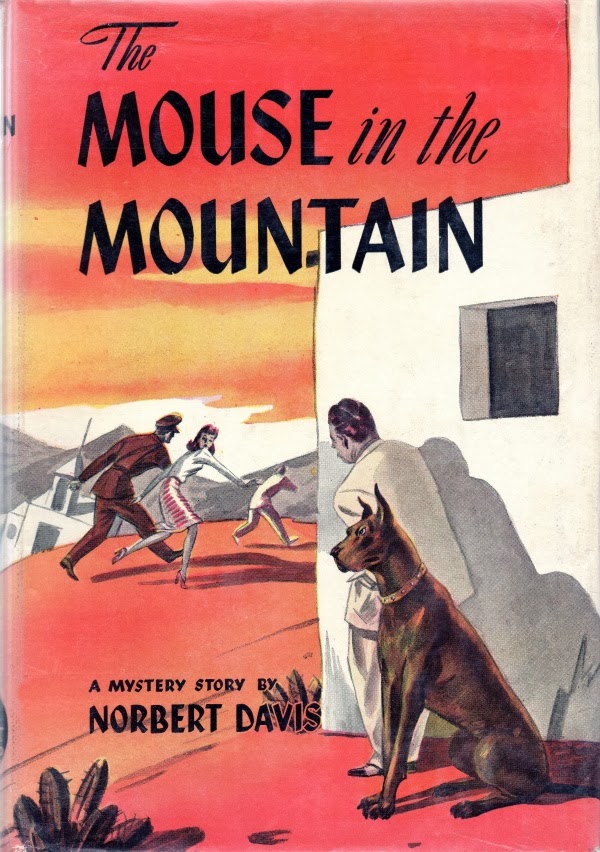

Dime store irony: The Mouse in the Mountain (1943)

Norbert Davis’ dime store detective novel The Mouse in the Mountain (1943) is surprisingly good. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s favourite novel was, perhaps, ahead of its time.

In terms of both atmosphere and narrative, Davis reaches heights comparable to the greats of the genre; Arthur Conan Doyle, but especially Agatha Christie. The story even takes a page out of the play book of the classical Greek tragedy: there is first, an ominous setting that remains largely unchanged throughout the story, the ancient Mexican town of Los Altos, perched on the side of a mountain overlooking a deep abyss. And second, the plot is for the most part driven by the actions of its characters, where each actions seems both inevitably caused by its precedents yet also the free choice of its agent. There is, however, one deus ex machina and it is a big one, advancing the plot in several ways: a massive earthquake that shakes Los Altos and cuts off the only route of escape from it. One is tempted to grant Davis this one, as it permits him to create that isolated, engrossing atmosphere that the story shares not only with Greek tragedy, but also Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, and Death on the Nile.

Like Christie’s as well, is Davis’ convincing handling of his eccentric protagonists, the corpulent and alcoholic Doan and his grumpy Great Dane, Carstairs. Splitting his detective in two allows Davis to venture deeper into the psyche of the detective-archetype, a familiar literary device to give a voice to the mute Freudian Id. But whereas one would suspect Carstairs, the dog, to be a stand in for Doan’s unsocialised desires, it is rather the other way around. It is the sensualist Doan, for instance, who seeks every opportunity to get drunk, thereby prompting growls and barks from the Superego Carstairs who then has to curb Doan’s blind desire and keep him focused on the task at hand.

Davis displays his ability to portray a convincing character throughout the novel, even when it comes to side-characters whose only function is comic relief, see for instance the hotel manager Timpkins who won’t stop protesting that he is a British subject. Davis use of language, finally, is wonderfully direct, and perhaps the main reason why Wittgenstein adored his novel. Take a sentence like “It was morning, and the sun was gleaming and grinning generously, regardless of earthquakes, murders, or even Hitler”. I can’t think of a writer, during or after WW2, high or low literature, who would play into the collective consciousness this directly to evoke an atmosphere. Is it a cheap trick? Yes, definitely. Does it work? That too.

One wonders why, as Ray Monk pointed out in his Wittgenstein bio, Davis was never able to transition from dime store novels to the big screen. Perhaps the duo of a corpulent alcoholic and his grumpy Great Dane was a bit too ironic for the aesthetic sensibilities of the 1940’s cinema public. If that is the case, what waves Davis could have made right now, when the ironic take on a classic genre has become a genre in its own right! I am talking not only of Knives Out, the entire oeuvre of Tarantino, many films of the Coen bros, but also the video game series Sam & Max which could just as well be inspired by the duo Doan & Carstairs. I cannot help thinking that Davis came too soon and, given his apparent suicide after a cancer diagnosis in 1947, left too early. A contemporary audience, which has, of course, lost the real taste for written stories, would perhaps be much more appreciative of Davis’ direct style of narration, combining the comic and the violent, the ironic with the cheesy.